Jaydn's lovely key art, and our game trailer (edited by me!)

Overview

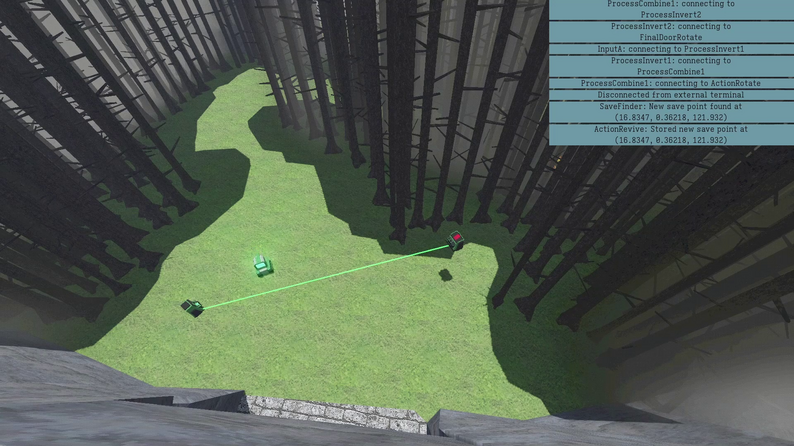

Butterfly Machine is a 3D puzzle game about a robot learning to reprogram itself.

I was responsible for the game design, direction, and programming, and also contributed some sound effects.

It was developed from December 2024 to May 2025 alongside Jaydn Jones, and features soundscapes from musician Ralph Banks. You can download the game for free on itch.io!

I filmed and edited a short documentary about the game's design and development.

Research-driven ideation

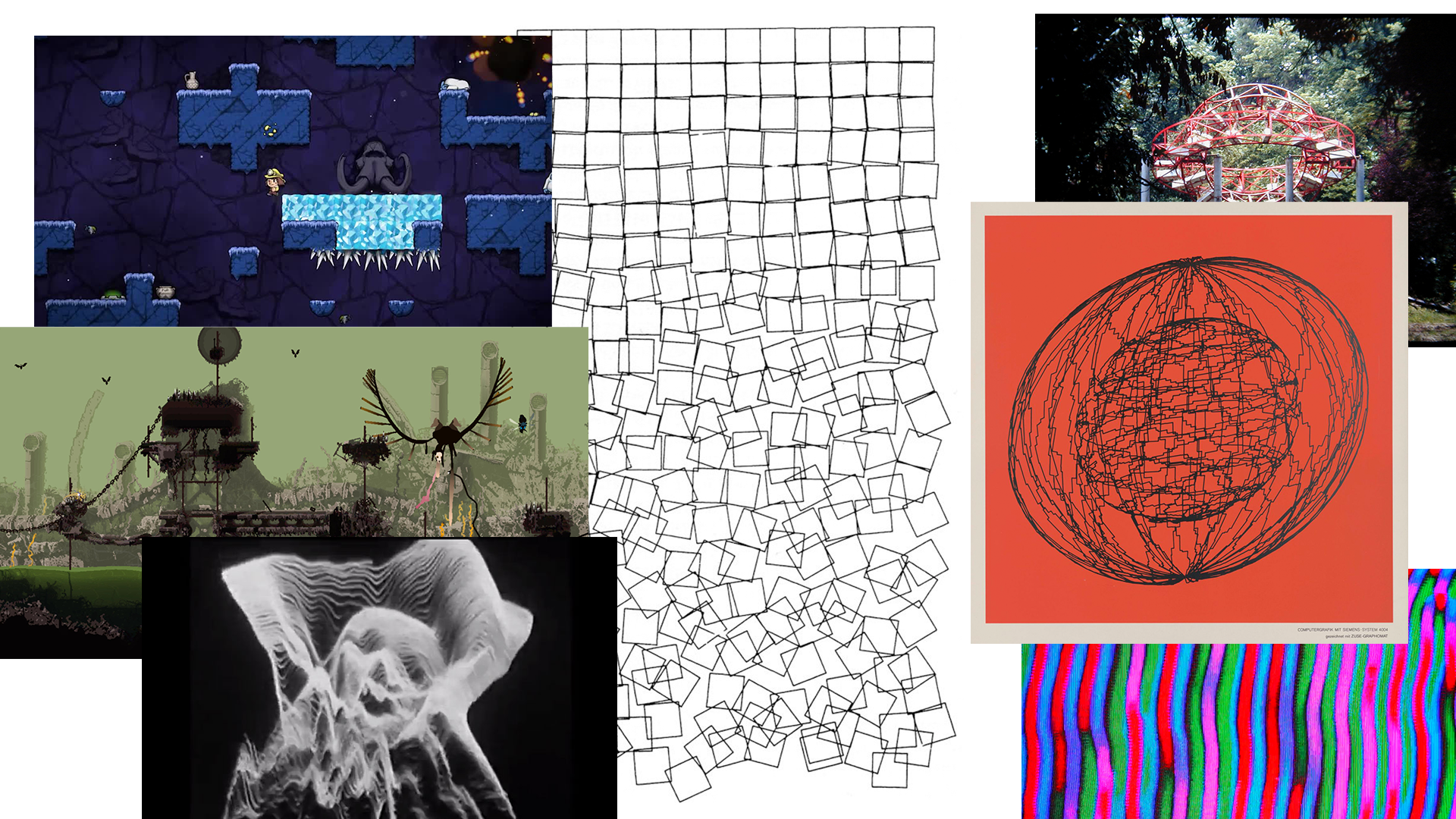

Our final university projects were inspired by external research: I chose to examine generative art, much of which uses digital logic to emulate organic structures and behaviour, emphasising faults in the systems to make the synthetic seem natural.

I looked into traditional line printer artworks, video synthesis, and modern implementations of generative logic in games such as Rain World and Spelunky.

I became interested in exploring player fragility in gameplay: could I tell a story by allowing the player to meddle with their internal systems? Can we give the player a tactile sense of responsibility over their life? Thus, we landed on the final pitch of having the player control a robot and modify its internal logic.

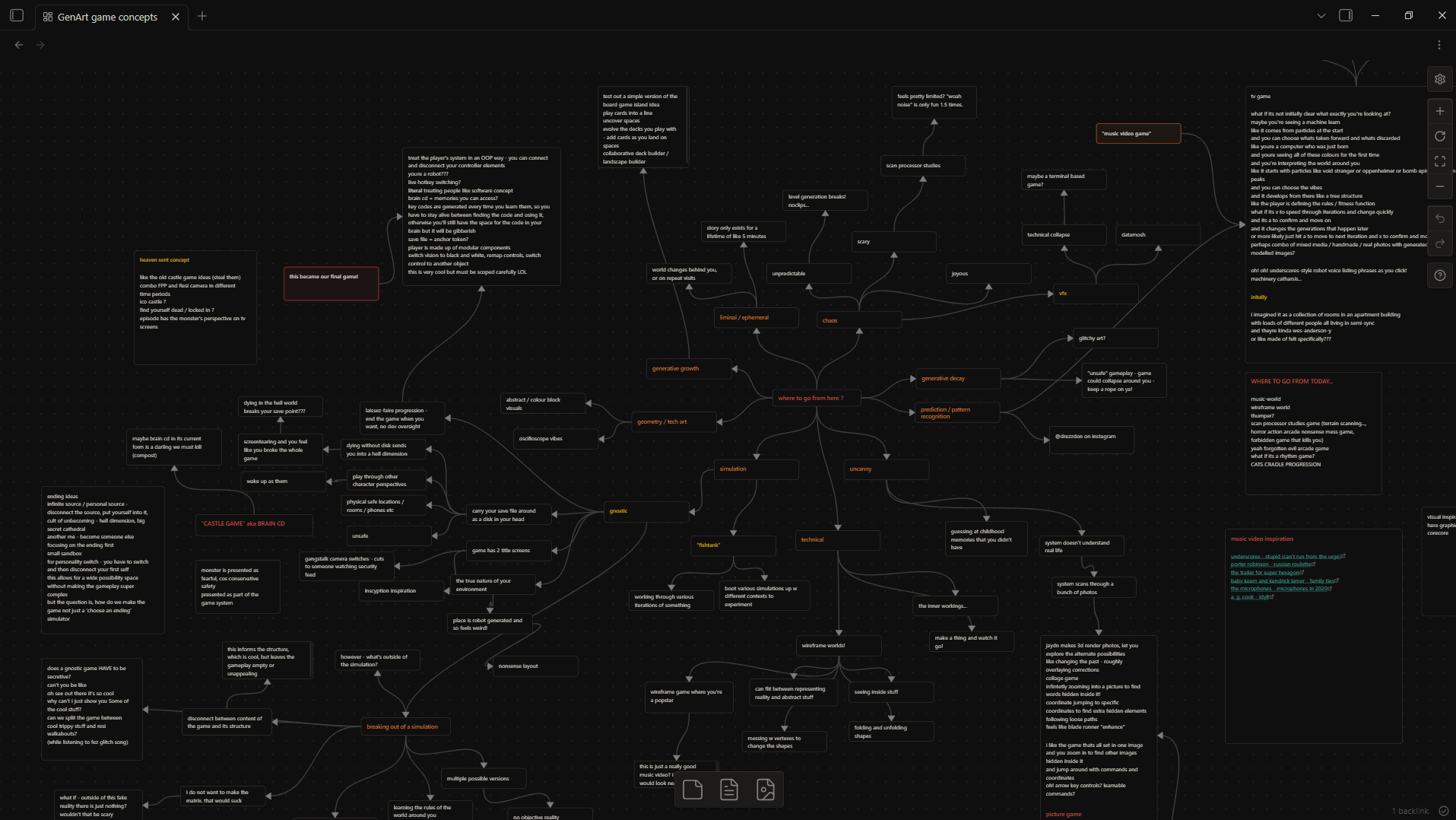

A mindmap of initial GenArt-inspired game concepts, including spooky photo-investigations, playable montage music videos, and nesting realities.

Defining the design

We used paper prototypes to nail down the design's opportunities and threats: we conducted a playtest that required the player to "sacrifice" their safety net in order to progress, this taught us that players can only feel good making "out-of-the-box" choices when they feel that it's truly their choice, which pushed us further into making a game about an open, "laissez-faire" system.

A simple paper prototype built to investigate players' approaches to self-sacrifice as a puzzle mechanic.

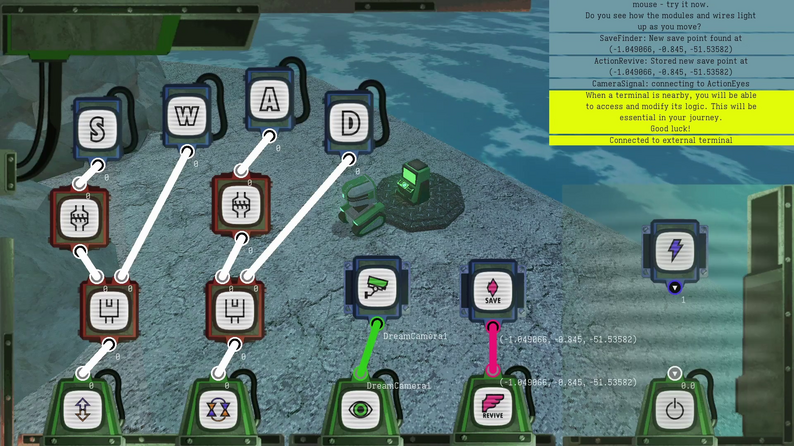

I also tested an early paper version of the game's programming mechanics, inspired by node-based visual scripting systems. It turned out that players enjoyed experimenting with the system even when just dealing with basic mechanics: our game was enjoyable just on paper!

A rough paper prototype testing the game's basic wiring mechanics: I had to ensure that experimenting with the system was fun before I committed to building it.

Jaydn and I then set out to carefully define our design pillars into a Game Project Proposal. We first defined the themes that we wanted the design to convey, and translated them into our design pillars:

- Responsibility for yourself: The player is in total control of the robot, and so must take care of it.

- Self-modification: The only way to progress is by the robot changing itself.

- Curiosity and fear: Modification is powerful but dangerous, and must be undertaken with care.

We also created three "philosophies" that helped us structure the experience:

- An Unbroken Journey: The player stays with the robot for the entirety of the game and their perspective never shifts away. The game is about the player's journey, and so it's important that the player feels connected to their avatar.

- Laissez-Faire: The game takes a "hands-off" approach to the player's interactions. If the player is to feel responsible for the robot, they must be free to succeed and fail of their own volition.

- Universal Logic: To support the a non-interventionist approach to gameplay, all moving parts in the game world should be a part of the same modular, open system. The robot is simply another part of the world.

So! Our goal was to create an open system, where the player could control their avatar completely, and use that to create tension.

The Design, Build, Test Cycle...

Our choice to make a puzzle game, especially one with unusual mechanics, necessitated an iterative development process based on regular testing and feedback. We would test the game with new players every week, making notes on how they engaged with and understood the systems, and address the feedback before the next tests. This was essential amid every step of development, and is the reason the game is playable at all.

This are the notes from just one playtest!

As an example, the game's tutorial went through a number of iterations...

- Our first version required the players to intuit all the logic of the system independently, and digest 10 new mechanics all at once. It was not popular.

- We changed it to introduce each mechanic individually, and build up the player's understanding. While they understood what the modules did, they only moved slowly and awkwardly.

- This was because players didn't realise that movement didn't have to be slow and awkward, as that was all they'd experienced. To remedy this, I started the robot with its modules pre-connected, allowing the player to move around normally, before removing the connections.

- Players now felt more comfortable learning the mechanics independently, as they had something to work towards.

Watching players teach themselves to walk became one of my favourite parts of the game.

A small selection of playtest notes from throughout development.

Nobody Told Me That UI Design Was This Difficult (They Did)

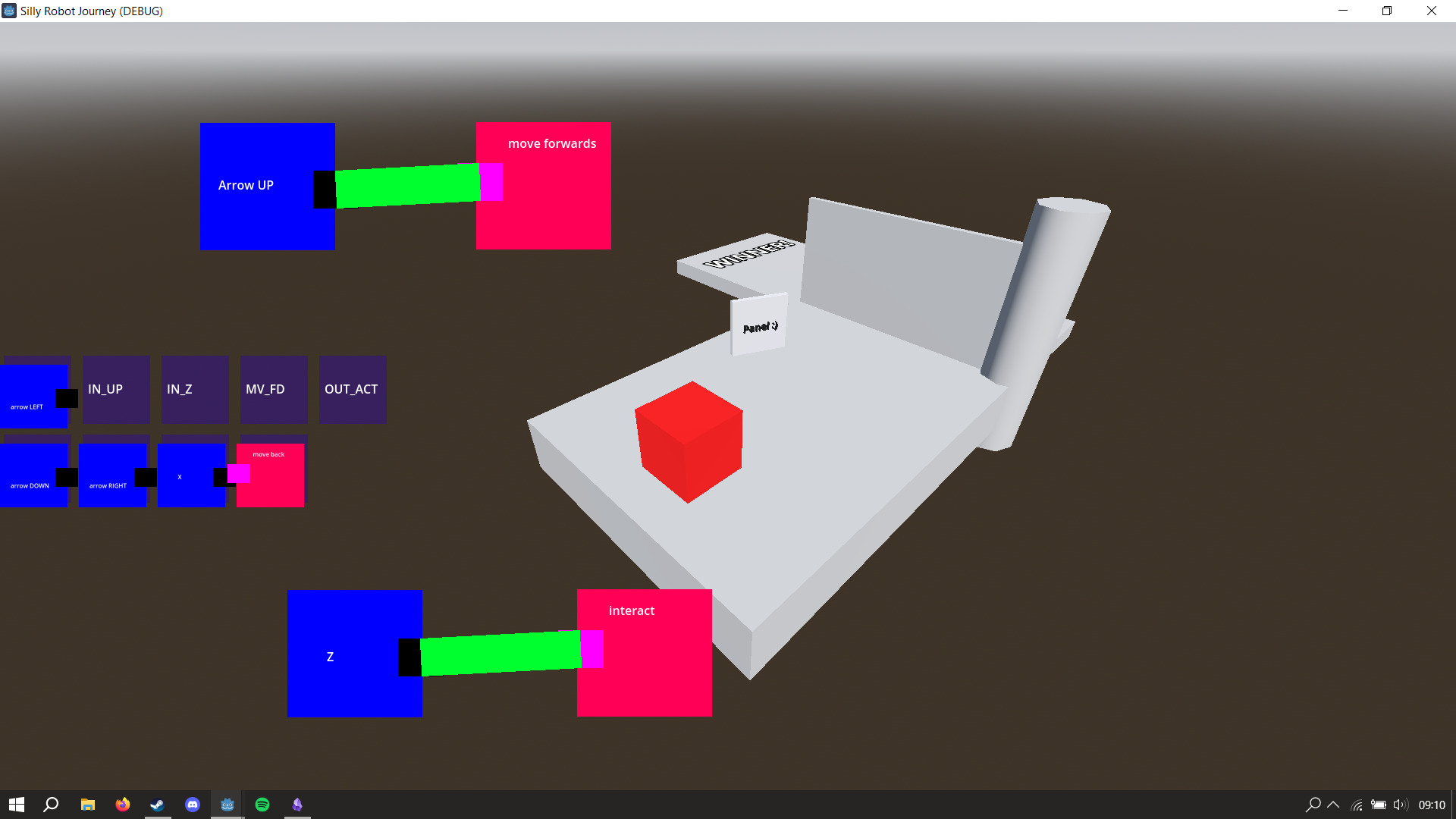

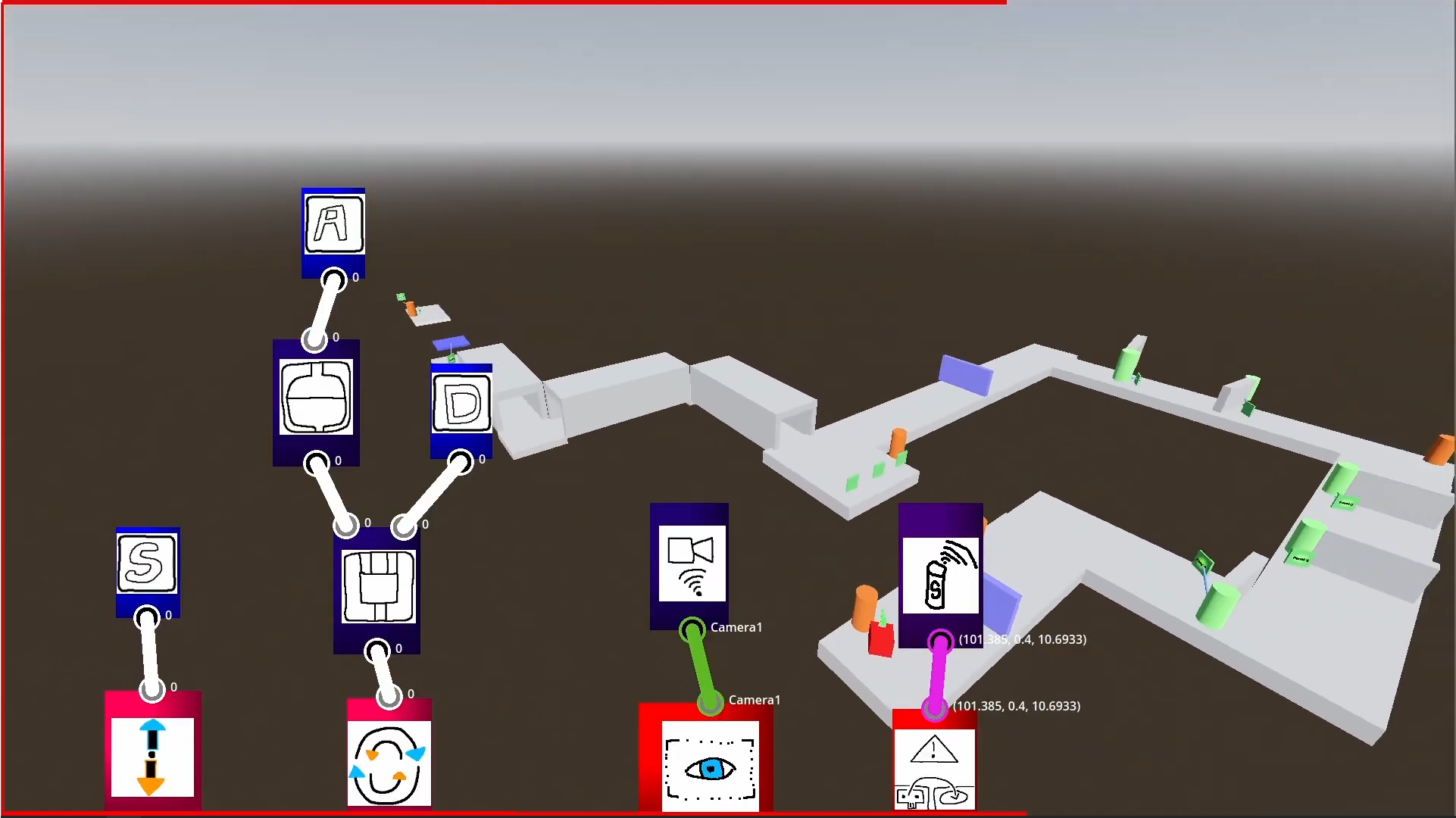

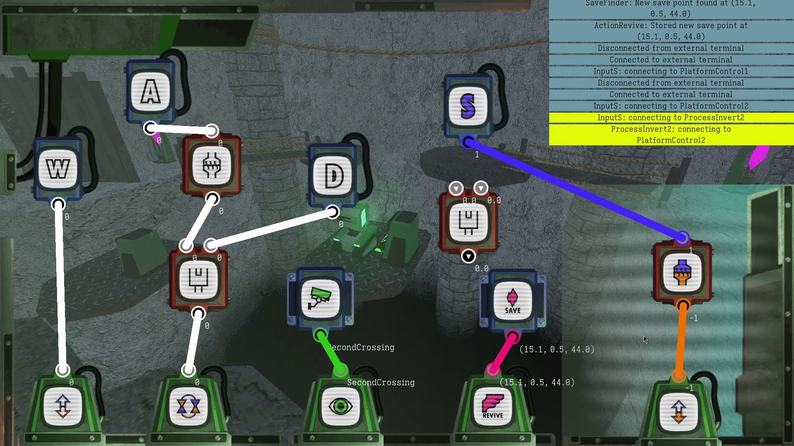

Every aspect of the game's user interface went through countless passes to ensure its purpose was clearly communicated to the player. We animated the modules and icons to make the data flow easier to understand, and eventually implemented a terminal-inspired readout for error messages to make the system more self-explanatory.

We wanted for players to have fun with the challenging puzzles, not a challenging user interface.

The user interface grew more detailed and self-explanatory as development progressed - and at some point I was forced to abandon the MS Paint graphics.

Task Wrangling

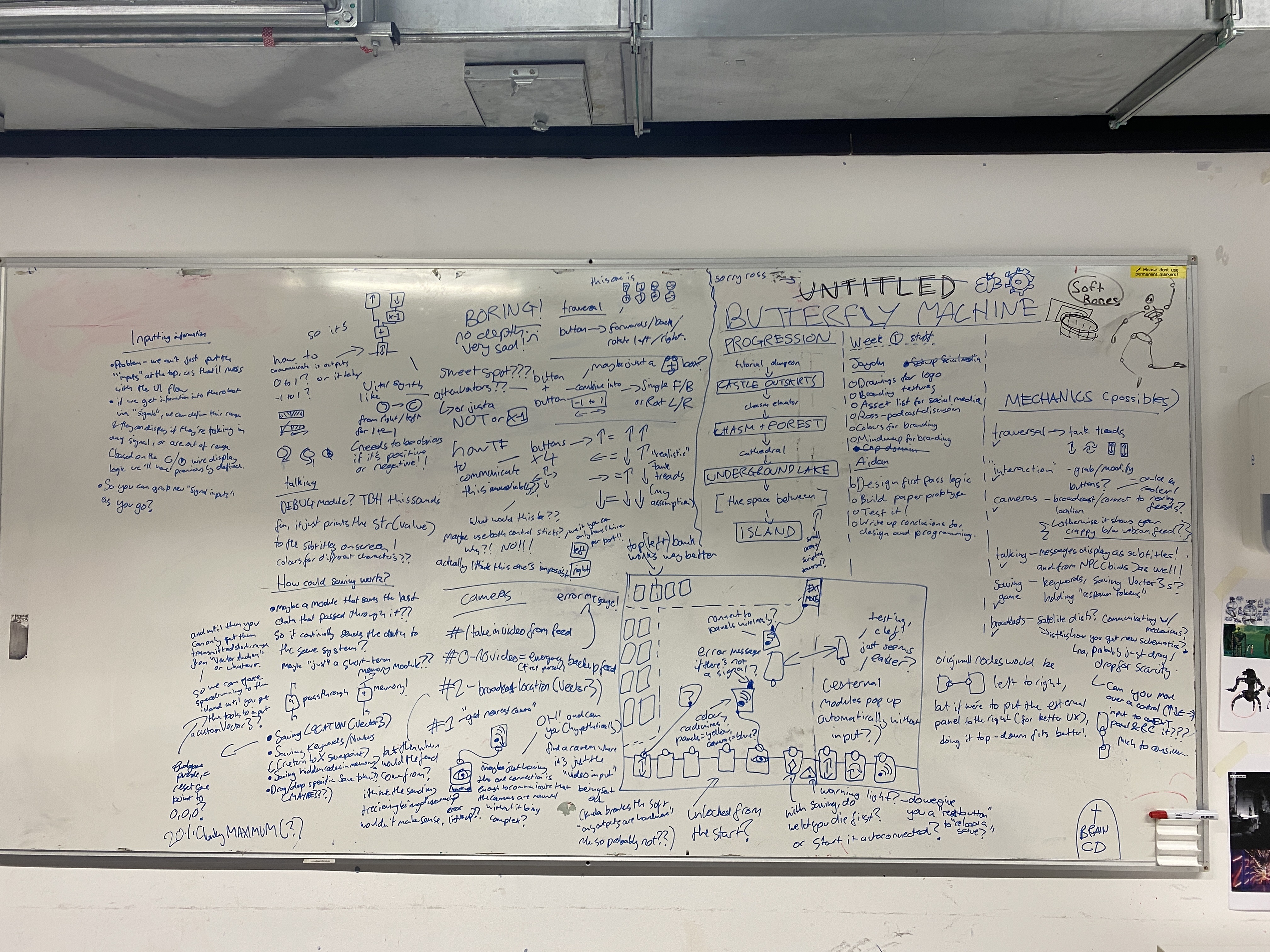

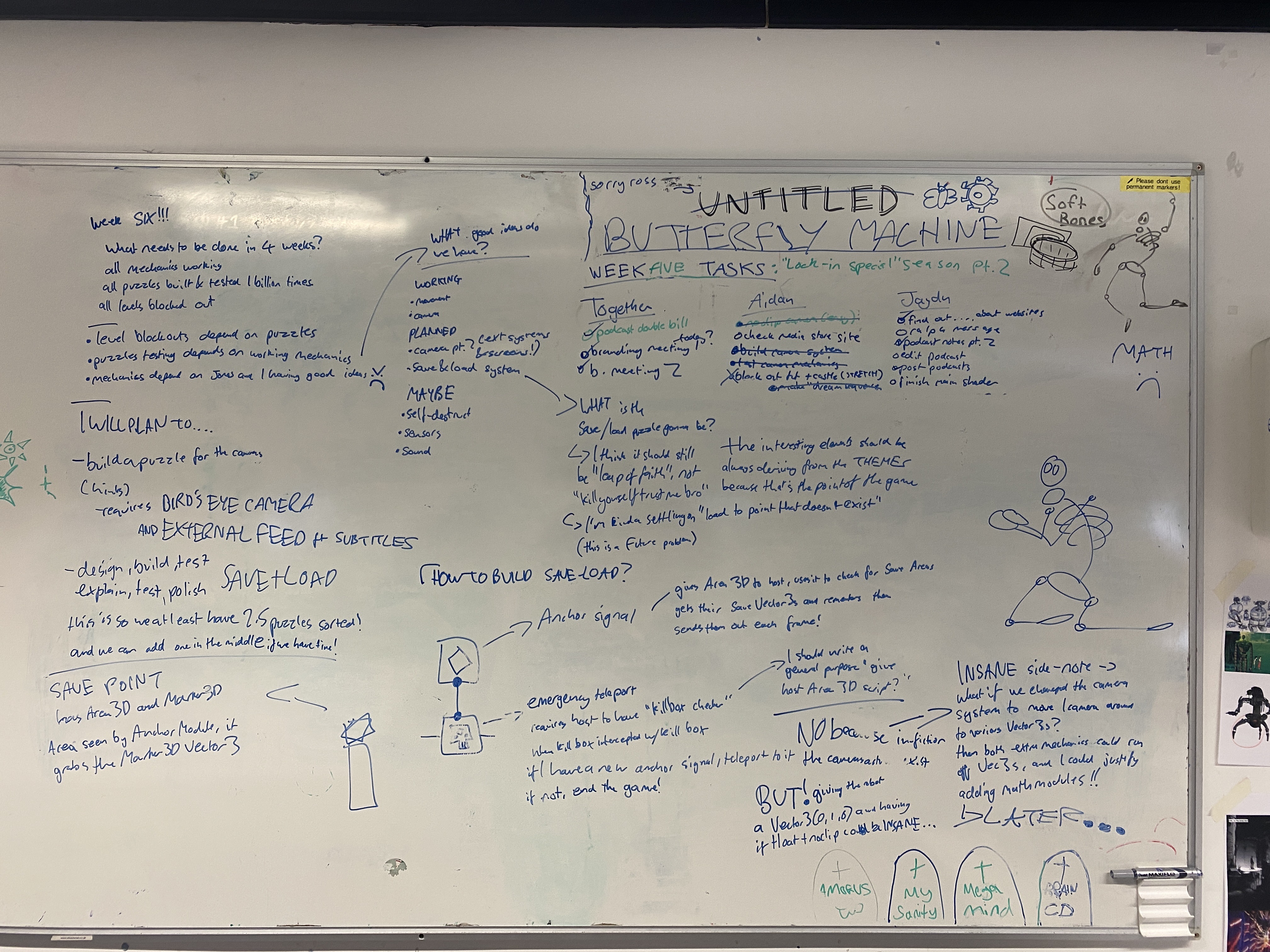

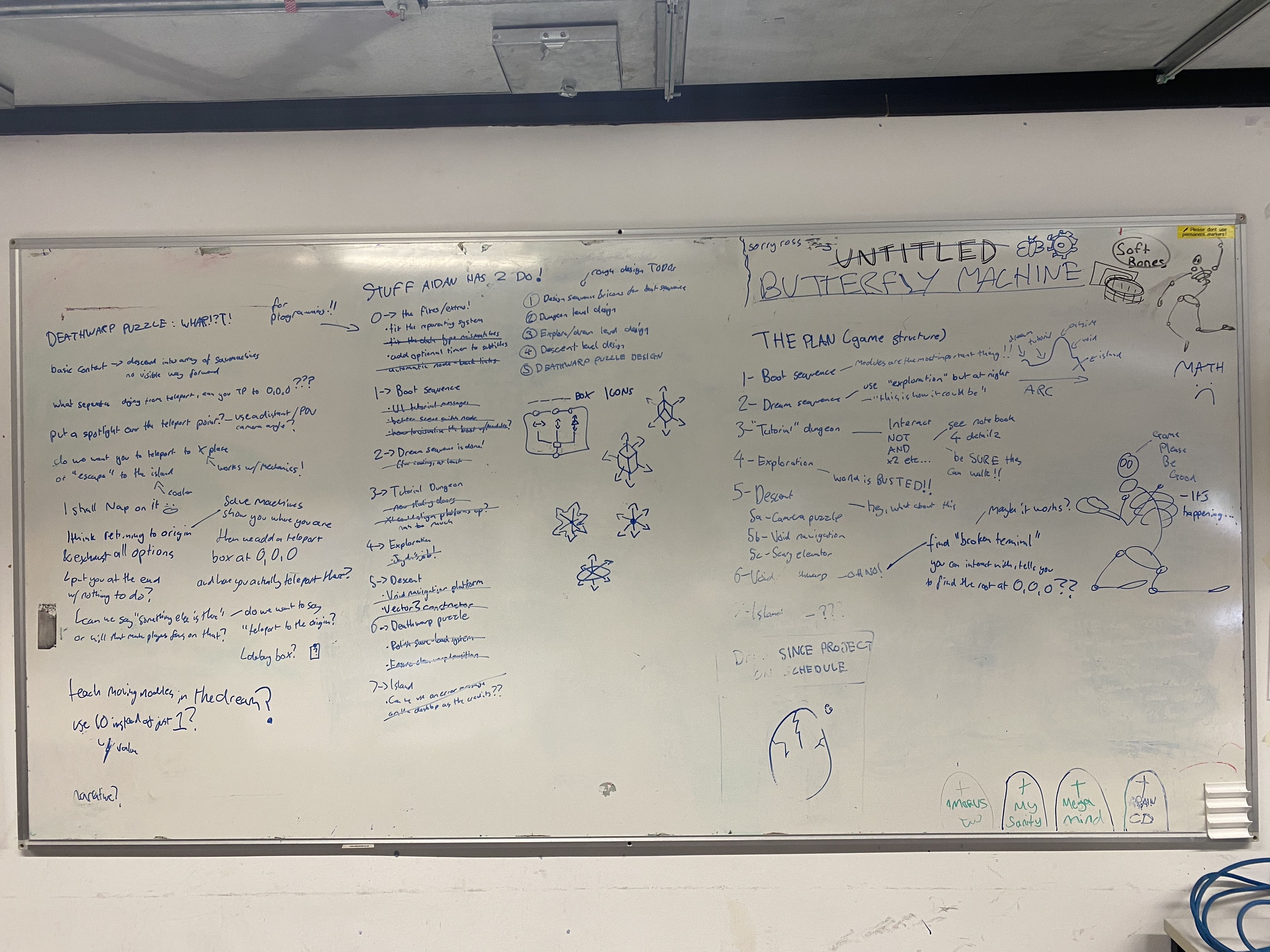

My development process relied heavily on Obsidian's Kanban boards for task tracking, without which the game would still be a prototype. Jaydn and I used Miro boards for online collaboration and setting weekly tasks, and would also regularly populate an entire studio whiteboard with inscrutable scribbles. We took weekly meetings and recorded semi-weekly podcast episodes to track our progress and identify problems.

The game ended up being quite small: we spent so long refining the tutorial that it ended up as half of the game! But this was an easy trade-off, it wouldn't have made sense to build more complex puzzle mechanics if players couldn't engage with them. Halfway through development, we stopped building new features and instead built an arc out of the pieces we had available.

A smattering of notes from throughout development.

Reflection

I'm very happy that the game turned out as well as it did, which I can credit to our pragmatic scheduling and relentless playtesting, without which the game would be neither completed nor fun. While Butterfly Machine is not for everyone, the people that connected with the game really enjoyed it, and engaged with the game's themes of responsibility and fragility. I look forward to applying everything I learned about onboarding, puzzle design and storytelling to my next project, which should hopefully take a brighter tone!

Speaking personally, Butterfly Machine means a lot to me. It's the first "big" game I'd made since 2021, the best puzzle mechanics I'd made at that point, an exploration of decontextualization and deconstruction through gameplay, and an opportunity to make a game with my best friend. I achieved everything I set out to do with the project. I hope you enjoy it too.

Our cabinet for Butterfly Machine, as exhibited in our London degree show!